10km Searchlight

Core Components and Their Roles

There are three key parts at play: the power supply, the ballast, and the bulb.

First, the power supply: I built a custom one because l couldn’t find anything commercially available at an affordable price. I used a full bridge rectifier (which converts AC into DC) and a capacitor to create a stable 340VDC supply using 240VAC input (in England we have 240V at the wall). For safety, I used a 1 mega-ohm resistor in parallel to the capacitor to enable it to slowly discharge after use; without that, the capacitor could store enough energy after powering off that it would be fatal if touched. Because of the high voltage, I had to ensure that everything was safe as any poorly insulated cables would pose a shock hazard. I also added an NTC (negative temperature coefficient) current limiter to prevent high inrush currents damaging my electronics.

Second, the ballast, it provides the initial jump start to get the bulb working and it regulates power to the bulb. At turn on the bulb can require 40kv to start. I bought the ballast second-hand, for cheap, on eBay. It was actually the second ballast I had purchased because I blew-up the first one during development. The ballast is controlled via the UART protocol and is used to ensure the bulb runs safely.

Finally, the bulb: I used a special kind that consists of a small fused quartz tube with a pocket of inert gases, mercury metal, and two electrodes. When the bulb is powered on, a short electric arc vaporises the mercury and excites the metal atoms. This excitation causes them to emit a wide spectrum of light. A bright 5mm LED typically draws 0.1W; by comparison, this bulb draws 270W, or 2700 times more power in a similar-sized footprint!

This bulb is incredibly dangerous if mishandled. Internally, it heats up to 1800 Fahrenheit and 3000 PSI (200 times atmospheric pressure) which, in case you didn’t realize, is ridiculously high. The fused quartz tube is used instead of glass because fused quartz can withstand higher temperature and pressure. However, without proper handling and cooling, if the fused quartz tube is overstressed, it could explode violently.

Reverse Engineering and Optics

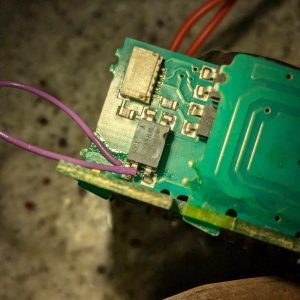

Normally, the electronics to run these bulbs are full of safety measures (ewww); I spent a lot of time reverse engineering and bypassing these safety measures because who needs those? I bought my first ballast from a repair shop and reverse engineered the PCB. Unfortunately, I very quickly killed it, so went to eBay for another one. With this second ballast, I learned how to isolate the controller from the high voltage supply and how to trick it into thinking a control board was connected. With this better understanding of how the ballast works, I chose to take an online course on high voltage safety training because I didn’t like the idea of dying. I know, shocking right?.

Then I moved on to studying the optics. The most common is a parabolic reflector which creates a beam of almost parallel light. In a ideal world, the rays of light within the beam would be perfectly parallel, but small manufacturing inaccuracies and thermal expansion inside the bulb create sources of error, and I measured an angle of 2 degrees on my beam (which later can be used to estimate the spotlight’s size at different ranges). The larger the reflector is and the smaller the light source is, the tighter the beam is; the small errors become less significant. Despite all the sources of error, these bulbs are made with higher precision than most other lighting systems because they’re typically used in projectors so they can achieve higher intensities in a similar footprint.

Final assembly and testing

All my research and reverse engineering took months. Only once I was confident in my knowledge, I purchased the components to study them. Using a multimeter and a lot of guesswork, I learned exactly how the ballast behaves at startup and how the power supply should be laid out for safety and efficiency. I also broke those components – both the bulb and the ballast – in the process (not on purpose).

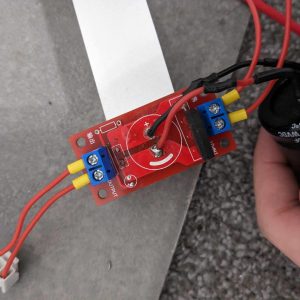

With my experience and knowledge, I set out to find another bulb and ballast that matched my requirements, I found them in my local area, for reasonable cost, and immediately set to work dismantling and identifying the exact boards and parts I’d need. I then bypassed the safeties on the ballast by installing a jumper wire and placing a resistor across the cooling detection pins. Using what I learned from the high voltage safety course, I created a well-insulated wiring harness and built the 340VDC power supply I designed. The final 340VDC power supply isn’t the most efficient but it’s cheap and effective. I wanted to create a mobile unit, so I purchased an inverter to convert 12VDC from a battery to 240VAC which is then rectified to 340VDC. All these conversions create losses, but they’re not significant enough to justify the cost of a more efficient supply.

Then came time to power up the final bulb assembly and start designing the case. I was able to power on my prototype just before leaving town for a family holiday, but I didn’t have enough time to finish the final unit. Ultimately, it will be a handheld box, with a dead man’s switch on the handle and a power unit mounted to a harness that I can wear on my back. It will weigh over 22lbs, with most of that weight coming from a 12V lead acid battery (I’d prefer to use a 12V LiPo, but they’re far more expensive).

Images:

- Another test setup which I used to power on the final version

- The first time light came out of the bulb while not being in my bedroom

- The beam is so bright it illuminates the cloud cover

- The shadow of the tree in the beam being projected onto the trees behind

- Me having a lovely time with the searchlight

Using a luxmeter and some tricky math as well as power measurements and lumen per watt values available online, I was able to determine the light’s intensity to be roughly 9.2 million candela, and output 17 thousand lumens. This delivers a range of 6km (3.7 miles), according to the ANSI FL1 spec (scroll to performance standards to see relevant information). For comparison, an average car’s high beams output 30,000 candela and 1500 lumens..

Conclusion

My target was to reach double digit ranges (in kilometres), but it feels okay for a first try; my second revision, which relies on different optics, is already in the works and should be much more intense.